#DEFINE SOLITUDE

Erano lettere mai spedite. E parole che raccontavano abissi di solitudine. Occhi profondi dentro i quali si perdeva il mondo triste dei manicomi di una volta. Era l’indifferenza che veniva restituita loro, ai dimenticati, uomini e donne indistintamente. Dimenticati per via di una presunta pazzia. Persone che supplicavano amore con piccoli gesti, piccole foto, piccole richieste tradotte in inchiostro come quella che diceva –non per guardarmi ma per amarmi-. Ad accogliere, a distanza di anni, quei desideri del cuore è stato un uomo che quella stessa solitudine ha voluto raccontarla dipingendola. Lui è Vincenzo Baldini e la sua arte è un percorso tutto coerente costruito intorno agli uomini e alle cose. E li racconta con la stessa dignità. E li guarda con la stessa sensibilità.

“Quando ero piccolo e abitavo con mia nonna in inverno a causa del freddo pungente lei era solita chiudere le finestre. Mi ricordo che fuori rimaneva un vasetto di terracotta e mi ricordo che dopo un po’ io aprivo la finestra, prendevo il vasetto e lo mettevo dentro casa perché secondo me aveva freddo lì fuori e non volevo lasciarlo solo.”

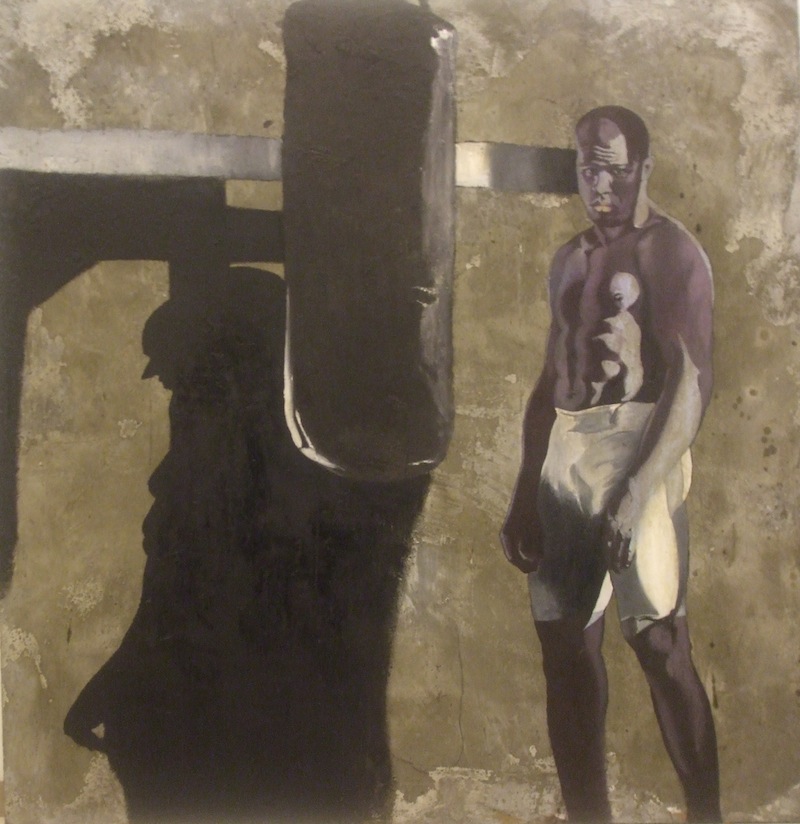

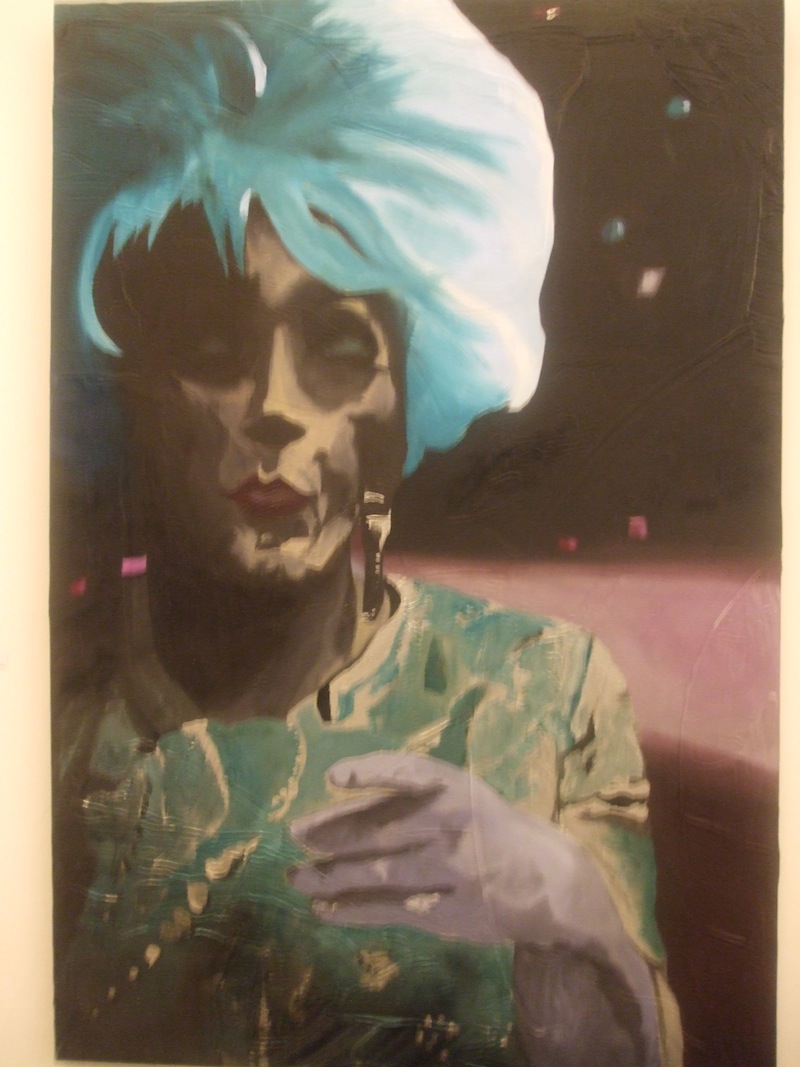

La solitudine delle case, sagome senza finestre e senza porte che si stagliano come monoliti nel buio color pece. La solitudine degli alberi o dei covoni di fieno in cui l’emotività rimanda alla poetica di Quasimodo -ognuno sta solo sul cuor del terra trafitto da un raggio di sole ed è subito sera-. La solitudine di spazi senza orizzonte e sconfinati. La solitudine di un pugile, uno di quelli che perde sempre, nel lasso di tempo malinconico in cui, dopo la sconfitta, si asciuga il dolore. La solitudine di una Drag Queen nel frangente breve in cui, levandosi il trucco, pensa alle poche ore che la separano dalla vita di tutti i giorni fatta di cose che non le piacciono.

La notte lava la mente – Vincenzo Baldini

La notte lava la mente – Vincenzo Baldini

La notte lava la mente – Vincenzo Bladini

La notte lava la mente – Vincenzo Bladini

La solitudine dei Dimenticati, la serie di opere che inizia a prender forma dal passo del vangelo secondo Matteo (21, 33-43) che recita –la pietra che i costruttori hanno scartato è diventata la pietra d’angolo-.

“Ho riflettuto per molto tempo sul significato della parabola, pensando che nel Vangelo ciò che viene scartato si trasforma in pietra d’angolo quindi in pietra importante nella costruzione di qualcosa. Il pensiero è andato subito alle persone ritenute dalla società non degne della società stessa e ho sedimentato questi sentimenti di esclusione, solitudine e abbandono per diversi anni. Poi il cerchio si è chiuso quando ho avuto modo di leggere un articolo di Repubblica che raccontava come durante la ristrutturazione del manicomio di Volterra fossero state ritrovate molte lettere scritte dai degenti ai loro cari ma mai spedite dal personale addetto”.

Erano decine di migliaia di lettere scritte tra la fine del ‘800 e il 1978 quando, grazie alla legge Basaglia, i manicomi in Italia vennero chiusi. Lettere dimenticate, al pari delle persone che le avevano scritte. Come tutti quelli che nell’attesa di una vana corrispondenza erano stati in fondo abbandonati due volte. Vincenzo avverte forte l’urgenza di farli sentire meno soli questi uomini. E come da bambino era solito portare dentro casa, al riparo dal freddo aspro dell’inverno, un piccolo vaso di terracotta, così adesso, da adulto, li va a cercare questi volti e gli regala un posto che li ripari dal freddo muto della loro solitudine. Sono fondi preparati con cemento le loro nuove case, fondi magmatici quasi, pesanti come il suo tratto quando disegna, la sua mano quando crea. Materia elaborata che ama la stratificazione e che sopra sé stessa ospita dipinti a olio. Figure che raccontano di un disagio interiore.

“Me li sono andati a cercare questi occhi, questi stessi volti che vedi qui raffigurati. Sono andato al vecchio manicomio di San Servolo, a Venezia, e ho fotografato tutto l’archivio. Con le foto ho realizzato i dipinti e ai dipinti, in maniera assolutamente arbitraria ed emotiva, ho abbinato stralci delle lettere ritrovate a Volterra. E ho come avuto la sensazione che questi uomini mi guardassero, come a dirmi grazie per una restituzione, un presunto risarcimento. Come a dirmi che era mio il merito di recapitare, finalmente, pur dopo tanti anni, le loro parole scritte. ”

I Dimenticati – Vincenzo Baldini

I Dimenticati – Vincenzo Baldini

Opere potenti e suggestive che hanno preso parte al progetto realizzato della Fondazione Sgarbi, il Museo della Follia, inaugurato a Matera nell’agosto 2012.

“Ora sento l’urgenza di fare qualcosa di etico, lavori che abbiano un peso etico. I piedi nudi dei poveri, per esempio. La povertà della povertà. Sento di doverla in qualche modo raffigurare.”

Come quel barbone e il Cristo, mesti e composti mentre arriva la sera, abbandonati da un Dio che non è venuto all’appuntamento e così ha abbandonato due volte. E a guardarli tutti insieme questi dipinti si sente riecheggiare dentro il grido acuto dell’amore, quasi ci chiamassero da dentro la vita, quasi ci costringessero a rinunciare all’immobilità dell’amore. Anche dipingendo.

Dio non è venuto all’appuntamento – Vincenzo Baldini

Dio non è venuto all’appuntamento – Vincenzo Baldini

Desidero ringraziare per la gentile intervista Vincenzo Baldini, pittore. www.baldinivincenzo.it

Video di Pasquale Russo

Traduzione di Chris Alborghetti

THE DUMMY MEETS VINCENZO BALDINI #DEFINE SOLITUDE

They were letters which had never been sent and words which told about the abyss of solitude. They were deep eyes within which the sad world of psychiatric hospitals was dying out. That was the indifference towards them, those who had been forgotten, men and women regardless, due to alleged mental illness. They were people who through small gestures, pictures or requests like those in ink that said –don’t look at me but love me– supplicated for love. With the distance of many years a man took all these wishes to heart. Thus, he decided to tell their solitude by painting it. This man is Vincenzo Baldini who interprets and expresses art through a coherent path built around people and things. He represents these folks as people of dignity and praise them for their sensitivity.

“When I was little and I lived with my granny, I remember that due to the bitterly cold winter she used to shut all windows. Nevertheless, there was a little clay flowerpot lying outside. So, shortly afterwards, I opened one of them to take flowerpot and bring it inside, since I thought it was cold as much as I didn’t want to leave it there on its own.”

The solitude of houses and their contours with neither windows nor doors that stand out like pitch-black monoliths. The solitude of trees or haystacks whose emotionality recalls Quasimodo’s poetical language –Everyone is alone at the heart of the earth, pierced by a ray of sunshine; and suddenly it’s evening.– The solitude of limitless spaces without horizons or that of a boxer who always loses the match, during the melancholy lapse of time when he wipes the beads of sweat from his forehead after having been defeated. The solitude of a drag queen in the brief instants when she removes her make-up and realises she is about to go back to her everyday life which is replete with things she dislikes. The solitude of The Forgotten, the series of works that starts to take shape from the passage of the gospel according to Matthew (pp. 21, 33-43) which says – The stone the builders rejected has become the cornerstone.–

“I reflected for a long time on the significance of the parable and I thought that what is rejected in the gospel transforms in a cornerstone and therefore in the foundation stone for anything which is going to be built or created. I gave a thought to those who are considered unworthy of society itself and I felt a sensation of exclusion, solitude and abandonment for many years. Then, one day after reading an article from La Repubblica (an Italian national newspaper) on the refurbishment of Volterra psychiatric hospital I closed the loop. In fact, there was written that the people who worked there during the refurbishment found many letters written by the inpatients to their loved ones. Nevertheless none of these letters were ever sent by the personnel in charge of it.”

We are talking about tens of thousands of letters written between the end of the nineteenth century and 1978 when, thanks to Basaglia law, psychiatric hospitals were closed down. Forgotten letters, forgotten like the people who wrote them or like all of those who longed for a regular correspondence and that because of the negligence of the personnel, got abandoned twice. Vincenzo has the urge to make these people feel less lonely. Like he used to do when he was a child, when he brought inside that little clay flowerpot that lay outside his granny’s, these days he is an adult who looks for these sort people and countenances in order to give them a shelter from the cold of their solitude. Their new homes then, are bases prepared with concrete, almost magmatic. Bases which are as heavy as his thick stroke when he paints them. They are materials which he works in such a way as to get layering upon which he oil paints figures which portray mental distress or discomfort.

“I looked for the eyes and countenances that you see depicted here. I went to the old psychiatric hospital in San Servolo (an island in the Venetian Lagoon) and I photographed all archive. With the pictures I took I made the paintings to which, in a way that is purely arbitrary and emotional, I attached to them bits of the letters that were found in Volterra. I got the feeling that these people looked at me as though they wanted to thank me for what they received from me as if it was a sort of compensation or restitution. I think, in their view, I had to take all the credit for delivering, after such a long time, their written words.”

Vincenzo’s works are outstanding, remarkable, appealing and valuable at the same time and are part of the project set up by Fondazione Sgarbi, il Museo della Follia (Sgarbi’s Foundation, the Museum of Madness), inaugurated in Matera (a city in Basilicata – Southern Italy) in August of 2012.

“Now I feel the urge to do something ethical works-wise. The poor and their bare feet for instance, in other words I feel the need to portray poverty-stricken people.”

As he did when he painted a tramp and Christ, both sorrowful, composed and dignified while the night was coming, both there abandoned by a God who stood them up and consequently abandoned them twice. When you look at all these paintings, you feel a high-pitched cry of love reverberating within you as if they called you from inner life and forced us to do without the stillness of love even when painting.

I would like to offer my special thanks to Vincenzo Baldini who gave the interview to me. www.baldinivincenzo.it

Video by Pasquale Russo

Translation by Chris Alborghetti